Soybean Export Landscape

Corn and soybeans are important feedstuffs in the livestock & dairy segments Compeer serves. At roughly a third of total Compeer outstanding volume, cash grain (mainly corn & soybeans) is the largest portfolio industry concentration. As such, fluctuations in the corn & soybean market materially influence many of our clients.

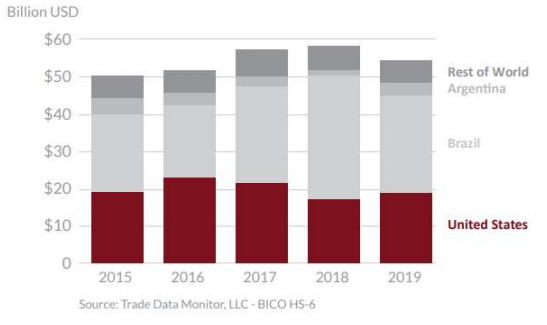

While both commodities are exported in significant quantities, roughly half of U.S. soybean production is sent abroad, a far higher proportion than corn. This reliance on exports to clear inventory from the market leaves soybeans pointedly more vulnerable to trade disputes and geopolitical machinations than other commodities.

Such geopolitical sensitivity was illustrated in 2018-19 as the U.S. and China levied retaliatory tariffs upon each other throughout their trade impasse. As tariffs were enacted, U.S. soybean volume to China largely ceased. Instead, U.S. production was mostly confined to other destinations, leaving overall export levels below pre-impasse volumes. Coupled with China's status as the global leader (by a huge margin) in soybean imports, and one can see how devastating the loss of market access was to producers, including Compeer grain clients.

Such geopolitical sensitivity was illustrated in 2018-19 as the U.S. and China levied retaliatory tariffs upon each other throughout their trade impasse. As tariffs were enacted, U.S. soybean volume to China largely ceased. Instead, U.S. production was mostly confined to other destinations, leaving overall export levels below pre-impasse volumes. Coupled with China's status as the global leader (by a huge margin) in soybean imports, and one can see how devastating the loss of market access was to producers, including Compeer grain clients. Amongst the commodities in the Compeer footprint, soybeans are more heavily reliant upon export activity to China than nearly all other commodities. The importance of the U.S./China Phase One agreement that ended the impasse cannot be overstated. For all intents and purposes, right now, China is the soybean export destination. U.S. production needs market access; otherwise grain producers will suffer financially.

Amongst the commodities in the Compeer footprint, soybeans are more heavily reliant upon export activity to China than nearly all other commodities. The importance of the U.S./China Phase One agreement that ended the impasse cannot be overstated. For all intents and purposes, right now, China is the soybean export destination. U.S. production needs market access; otherwise grain producers will suffer financially.

U.S. soybean imports comprised roughly 30 percent of the entire Chinese import market with South America providing most the rest. In fact, Brazil, the U.S., and Argentina are the largest producers and exporters of soybeans globally. Limited major production areas coupled with a single dominant buyer creates an interesting market structure. As the dominant importer, China largely dictates the market.

Outside the trade impasse, China has specific timeframes when entering the market. U.S. production is largely purchased at/near harvest, when prices tend to be more favorable. Likewise, Chinese purchases then shift to the South American production centers to take advantage of favorable harvest prices there. With such a concentrated market structure, hiccups in supply/demand create unique situations. One such situation involved Brazil last year. As the global leader in soybean export activity, it raised eyebrows when a load of U.S. soybeans was allowed into Brazil last year. It isn't likely that Brazil will become an importer of soybeans anytime in the future, but low inventories, coupled with strong domestic demand from protein segments, yielded a situation where it made sense to bring U.S. soybeans into the country.

With such a concentrated market structure, hiccups in supply/demand create unique situations. One such situation involved Brazil last year. As the global leader in soybean export activity, it raised eyebrows when a load of U.S. soybeans was allowed into Brazil last year. It isn't likely that Brazil will become an importer of soybeans anytime in the future, but low inventories, coupled with strong domestic demand from protein segments, yielded a situation where it made sense to bring U.S. soybeans into the country.

Attempting to diversify the marketplace, the U.S. continues to foster relationships with other potential export destinations, beyond China. This work is ongoing and important work, made more urgent during the trade impasse. While several promising markets exist, it will take time and resources before significant impact is seen in the marketplace. Even if successful, China is likely to continue to drive the market, due to the volume of imports. That said, in time, a more diverse export market could help to offset some of the geopolitical risk posed by the China relationship.